Grok | The End

Hollywood has a problem

No one wants to see its movies

No one in the industry can seemingly find work

And the future doesn’t look much better

The story of how we got here starts almost two decades ago

When Americans stopped another activity

Buying DVDs

Hollywood’s solution?

China

The Pivot to China

In the early 2000s, Americans began to slowly stopped going to the movies. Hollywood was able to make up loss in revenue through DVDs and TV residuals. By 2010, those markets were starting to dry up as well. In 2008, China burst onto the global stage with its impressive opening ceremony for the Summer Olympics in Beijing. Hollywood thought the Chinese audience had arrived and was ready to throw them a lifeline.

Eager to cash in on millions of new viewers, studios doubled down on spectacle-driven franchises and sequels at the expense of original storytelling. Studios were worried that dialogue-heavy dramas would likely get lost in translation, and shifted their focus to visual extravaganzas. These bets at the time made sense, the extra box office revenue from China could spell the difference between a flop and a major success. Studios had to ensure their content to “traveled well” internationally.

In practice, this meant assembly-line filmmaking: every year brought more superhero sequels, “Fast & Furious” installments, and franchise spin-offs engineered to captivate global audiences, especially Chinese moviegoers. Hollywood executives spoke of franchise building as if it were foolproof and self-renewing – a kind of creative recycling that could be repeated indefinitely. By 2016, the international market (led by China) made up roughly 60% of Hollywood’s box office, up from only 30% in 1991.

Appeasing the Dragon: Censor-Approved, China-Friendly Films

To fully tap China’s market, Hollywood went beyond just favoring blockbusters – it actively altered content to appease Chinese censors and tastes. Studios “bent over backward” to avoid China’s red lines, often preemptively sanitizing scripts. In a telling example, the 2010 remake of Red Dawn originally featured Chinese invaders, until Chinese officials caught wind. The studio spent over $1 million in post-production to digitally change the villains to North Koreans, rather than risk angering Beijing. Never mind that a North Korean invasion made no sense; studios had to preserve access to China’s audience no matter the cost.

Overt Chinese product placement and scene additions also became common. Marvel’s Iron Man 3 (2013) released a special China-only cut featuring extra scenes of Chinese doctors heroically saving Tony Stark’s life – footage so out-of-place that Chinese audiences ridiculed it as shameless pandering. Michael Bay’s Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014) had scenes in Texas with Chinese ATMs and showcased Chinese officials coming to the rescue of Hong Kong; a sequence added at Beijing’s request to portray China as the savior in a climactic battle. Such concessions paid off financially, Age of Extinction raked in a then-record $301 million in China.

Character casting was also tweaked to court Chinese viewers. Chinese stars began popping up in minor roles in big Hollywood films (Fan Bingbing in Iron Man 3, Li Bingbing in Transformers 4, etc.), and scenes were shot in China to flatter local audiences. Scenes that might offend China were cut or changed:

Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End: a Chinese pirate’s scenes were trimmed for “looking too ugly”

Men in Black 3: Removal of 13 minutes of footage featuring aliens disguised as Chinatown workers

Top Gun: Maverick: Paramount initially censored flag patches for Taiwan and Japan on Tom Cruise’s jacket and replaced them with nondescript symbols to avoid upsetting Chinese nationalists. (Notably, the flags were restored in the 2022 final cut, by which time Hollywood’s mood on China had shifted.)

American-Chinese co-productions became another pathway to please Beijing. The most notorious was 2016’s The Great Wall, a fantasy epic directed by China’s Zhang Yimou and starring Matt Damon. Billed as a East-West collaboration, it was built a western movie for a Chinese audience, complete with a western hero dropped into Chinese legend. Unfortunately for the producers, the film flopped and was lambasted as a creative misfire. Reviewers stated the film had “no soul…no emotion, and a threadbare narrative”, proving that throwing big budgets and stars together isn’t a substitute for genuine storytelling. As one critic quipped, The Great Wall exemplified a marriage between China and Hollywood “built on cash rather than creativity”.

The Rise of Chinese Blockbusters

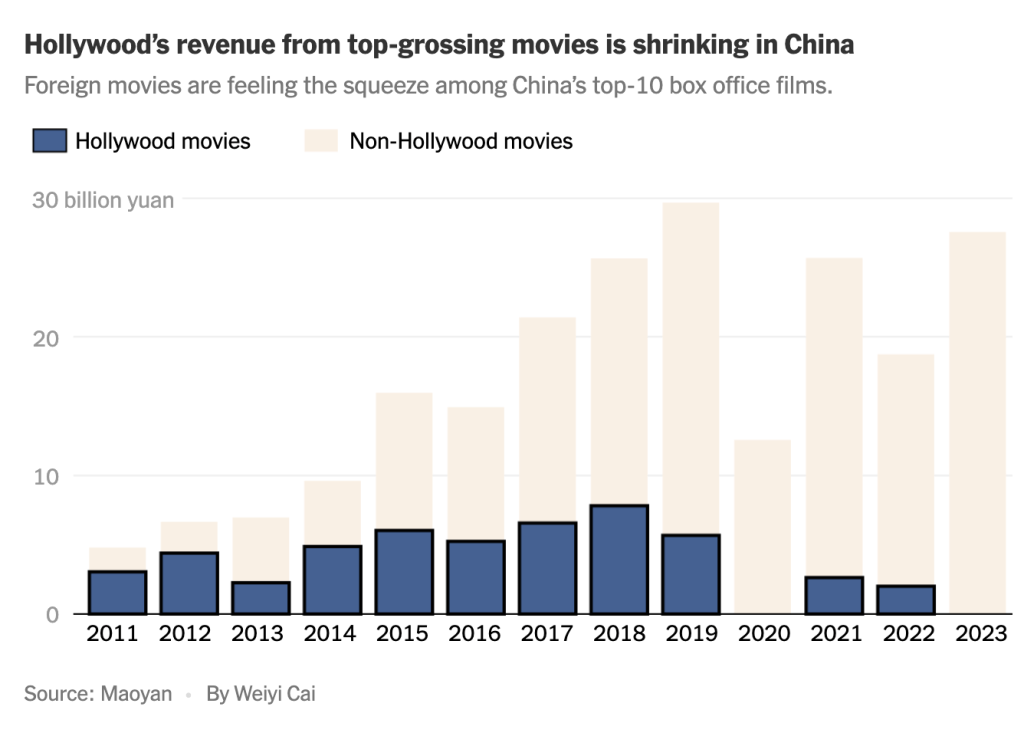

Just as Hollywood thought it had found a golden goose, the Chinese audience began to lose its appetite for Hollywood fare. In recent years, Chinese moviegoers – once enthralled by Transformers and Marvel heroes – have increasingly favored homegrown films. In 2012, 7 of China’s top 10 box office hits were American. But by 2023, not a single U.S. film made China’s top 10 despite a parade of Hollywood sequels that year.

Even surefire franchises like Fast & Furious, Mission: Impossible, and Marvel’s Spider-Man underperformed or got edged out by Chinese hits. The age of Hollywood dominance in China is emphatically over.

I don’t think we’re gonna ever go back to those earlier days

“I don’t think we’re gonna ever go back to those earlier days,” said USC professor Stanley Rosen, noting that even when Hollywood blockbusters still draw crowds in China, their numbers are way down from the peak. Several factors fueled this reversal. Chinese audiences simply got bored with Hollywood’s repetition. Years of formulaic storylines and predictable hero’s-journey arcs left viewers satiated. As one Chinese filmgoer bluntly put it, “Hollywood movies can no longer bring novelty to Chinese audiences”. At the same time, China’s domestic film industry hit its stride, delivering culturally resonant stories that international blockbusters lacked. From nationalistic action spectacles like Wolf Warrior 2 (which grossed an astounding $870+ million in China alone) to sci-fi epics like The Wandering Earth, local filmmakers proved they could match Hollywood on production value and connect better with Chinese sensibilities.

Beijing’s policies also nudged the shift. The Chinese government, after years of courting Hollywood, began to emphasize self-reliance in media. Import quotas remained tight (34 foreign films a year) and sometimes top U.S. titles were denied release dates for murky reasons. During trade and diplomatic spats around 2019, approvals for big American movies stalled, creating opportunity for Chinese films to grab screens. Major Marvel films (Black Widow, Shang-Chi, Eternals) were absent from Chinese theaters for several years, whether due to content disputes or geopolitical tension. Meanwhile, patriotic local films were actively promoted. The result: Chinese studios no longer needed Hollywood to fill seats, they had their own blockbuster films doing the job. By 2024, domestic productions regularly commanded 80%+ of China’s total box office, relegating Hollywood imports to a minor share.

Financial and Creative Fallout in Hollywood

Hollywood’s reliance on China had propped up its big-budget habits. As the Chinese market has dried up, particularly post-Covid, the consequences have hit hard. Studio executives have been forced to recalibrate budgets and expectations in light of China’s downturn. Projects once greenlit with the assumption of a lucrative Chinese run can no longer count on that payoff. By late 2023, insiders acknowledged that franchise sequels must be produced more frugally because China’s revenue boost is no longer a sure thing. For example, 2014’s Transformers: Age of Extinction earned $280 million in China, whereas 2023’s Transformers: Rise of the Beasts made barely a third of that. That kind of decline drastically dents a film’s global gross, which in turn means less money to fund the next installment. The era when Chinese grosses could rescue a middling U.S. performance (as happened with films like Warcraft and Pacific Rim) has ended. Having less money available from franchise hits has made Hollywood even more risk-averse creatively. It has become a vicious cycle: the less Hollywood experiments, the more audiences everywhere tire of the formula.

The Next Disruption: AI and New Global Players

Just as Hollywood grapples with the loss of the Chinese market, another upheaval is on the horizon: artificial intelligence. Creative AI will change how movies are made, and may even allow emerging markets to leap ahead while Hollywood hesitates. The recent Writers’ and Actors’ Guild strikes in the U.S. underscore Hollywood’s trepidation about AI. The new SAG-AFTRA contract, for instance, mandates consent and pay for using an actor’s AI-generated likeness or voice. In Hollywood, AI is seen as a double-edged sword: a tool for efficiency, but also a threat to jobs and artistic integrity. Consequently, the industry has been cautious and slow-moving in fully embracing AI-driven production.

In the era of generative AI films, imagination will become the most crucial factor

Elsewhere, that’s not the case. Countries like South Korea are charging forward, unencumbered by Hollywood’s legacy constraints. Korean filmmakers have already begun testing generative AI to create content faster and cheaper. We are approaching a future where imagination trumps budget. As a Korean film festival director noted, Hollywood dominated in the past due to its huge capital, “but in the era of generative AI films, imagination will become the most crucial factor,” especially as AI drastically cuts production costs.

South Korea’s entertainment industry, already known for innovation in K-dramas and K-pop, is quickly integrating AI – from de-aging actors and voice cloning to entirely AI-generated actors and scripts. And unlike Hollywood, they face fewer union roadblocks when experimenting with these technologies. Other emerging markets and creators worldwide are likely to follow suit, adopting AI to produce content that’s fresher, more tailored to local tastes, and made at a fraction of Hollywood’s usual cost. Without WGA/SAG-style limitations, these players can iterate rapidly, using AI for everything from pre-visualization to marketing. For instance, Chinese and Korean productions can freely use AI tools to analyze scripts and even recommend shooting locations and casting choices within seconds – innovations that traditional Hollywood productions are only beginning to explore.

Hollywood, caught on its back foot, may find itself disrupted once again just as Netflix and streaming upended the old studio system’s distribution model. Now AI-empowered filmmakers from Seoul to Mumbai could start churning out movies and series that capture global audiences. If Hollywood’s past decade was defined by chasing one foreign market (China) and stretching old IP to its limit, the coming decade might be defined by chasing new technology and competing with a flood of AI-assisted content from all corners of the globe.

The End of the Line?

Hollywood’s post-2010 romance with the Chinese market is a cautionary tale of short-term gains over long-term vision. In chasing China’s money, Tinseltown recycled its ideas to death, mistaking a financial strategy for a creative one. Once China’s audiences moved on and its government shut the door, Hollywood was left with battered finances, a backlog of stale sequels, and a creativity deficit.

Yet, within every reckoning lies an opportunity. Hollywood can learn from this collapse of the illusion. The solution isn’t to double down again on another formula, but to rediscover real creative risk-taking, the kind that made Hollywood movies iconic in the first place. In cinematic terms, that means investing in original voices and stories that aren’t just engineered by committee for four-quadrant appeal. It means making movies that stand out, not just scale up.

The coming wave of AI and the rise of global competitors will not wait for Hollywood to catch its breath. Studios that spent the last decade chasing trends abroad now face the prospect of being chased by nimbler creators abroad. The playing field is leveling: massive budgets and legacy IP libraries are no longer guaranteed advantages when an independent filmmaker with AI tools can craft a high-concept film in days, or when Seoul’s studios can produce a hit series at a fraction of the cost. In this new era, Hollywood must do what it once did better than anyone…innovate or die.